Family-based Obesity Prevention for Infants: Design of the "Mothers & Others" Randomized Trial

- Enquiry commodity

- Open Admission

- Published:

Domicile-based intervention for non-Hispanic black families finds no significant difference in infant size or growth: results from the Mothers & Others randomized controlled trial

BMC Pediatrics volume 20, Article number:385 (2020) Cite this article

Abstract

Background

Non-Hispanic black (NHB) infants are twice as likely equally not-Hispanic white infants to feel rapid weight proceeds in the first six months, yet few trials accept targeted this population. The current study tests the efficacy of "Mothers & Others," a home-based intervention for NHB women and their study partners versus an attending-control, on infant size and growth between birth and 15 months.

Methods

Mothers & Others was a two-group randomized controlled trial conducted between November 2013 and December 2017 with enrollment at 28-weeks pregnancy and follow-up at iii-, 6-, nine-, 12-, and 15-months postpartum. Eligible women cocky-identified as NHB, English-speaking, and 18–39 years. The obesity prevention group (OPG) received anticipatory guidance (AG) on responsive feeding and intendance practices and identified a study partner, who was encouraged to nourish home visits. The injury prevention group (IPG) received AG on child safety and IPG partners only completed study assessments. The primary delivery aqueduct for both groups was six dwelling house visits by a peer educator (PE). The planned master effect was hateful weight-for-length z-score. Given meaning differences between groups in length-for-historic period z-scores, infant weight-for-age z-score (WAZ) was used in the current study. A linear mixed model, using an Intent-To-Treat (ITT) data set, tested differences in WAZ trajectories between the ii handling groups. A not-ITT mixed model tested for differences past dose received.

Results

Approximately 1575 women were screened for eligibility and 430 were enrolled. Women were 25.7 ± 5.3 years, mostly single (72.3%), and receiving Medicaid (74.iv%). OPG infants demonstrated lower WAZ than IPG infants at all time points, but differences were not statistically significant (WAZdiff = − 0.07, 95% CI − 0.twoscore to 0.25, p = 0.659). In non-ITT models, infants in the upper end of the WAZ distribution at nascence demonstrated incremental reductions in WAZ for each home visit completed, but the overall test of the interaction was not significant (F 2,170 = 1.41, p = 0.25).

Conclusions

Despite rich preliminary data and a strong conceptual model, Mothers & Others did not produce significant differences in infant growth. Results suggest a positive bear on of peer support in both groups.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT01938118, 09/x/2013.

Background

There has been an approximate 60% increment in overweight amid infants and toddlers in the by few decades [one, 2], a business organization given associations betwixt large infant size and rapid postnatal growth with subsequent child and adult overweight [3, 4] and hereafter co-morbidities [five, 6]. Behavioral determinants associated with big babe size and rapid growth include short durations of exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) or any breastfeeding (BF) [7], introduction of complementary foods (CF) earlier iv months [eight, ix], short sleep elapsing [10, 11], early emergence of potentially obesogenic diets [12,13,xiv,15], and high levels of screen-time [xvi,17,eighteen]. Importantly, there is growing evidence on modifiable factors associated with early life feeding and care behaviors, including infant feeding attitudes, intentions, self-efficacy, and social support [19,twenty,21,22,23,24], also as parental feeding styles [25, 26] and appropriate estimation of infant fussiness [27,28,29].

One priority population for intervention is non-Hispanic black (NHB) infants. As compared to non-Hispanic white (NHW) infants, NHB infants take a higher prevalence of obesity [two], are twice as likely to feel rapid weight gain in the first half-dozen months [30], and are less probable to exist breastfed [31]. Studies among low-income, NHB mothers have documented a prevalent feeding pattern of formula, solids, and juice in the first 3 months [28, 32, 33], and NHB infants are more than probable than NHW infants to have a daily slumber duration of < 12 h, to take a Boob tube in the bedroom, and to consume sugar-sweetened beverages and fast food [30].

The purpose of the electric current study is to report the effectiveness of "Mothers & Others," a home-based, responsive feeding and intendance intervention delivered by trained peer educators (Human foot) to NHB meaning women and their study partners. The intervention began during the 2nd trimester of pregnancy and continued through 12 months postpartum, with concluding follow-up at 15 months. To increase social support for the targeted behaviors, intervention women identified a written report partner at baseline, who was encouraged to attend all home visits and was provided their own set of intervention materials. The attention-command group received a like number of contacts focused on injury prevention and identified a study partner, who just completed study assessments. Specifically, nosotros compare the consequence of the intervention versus the attention-control on the main outcome of infant size and growth between birth and 15 months postpartum.

Methods

Overall study pattern

Mothers & Others was a two-group randomized controlled trial (RCT) conducted between November 2013 and December 2017 among 430 NHB pregnant women and families living in central Due north Carolina. The report began when women were at 28 weeks gestation (baseline) and had a concluding assessment when infants were 15 months old, with acting assessments at birth, 1, iii, vi, 9, and 12 months of infant historic period. The primary commitment aqueduct was home visits past PEs. Institutional review lath approval has been granted by the University of North Carolina, Office of Homo Research Ethics.

Participants and recruitment

Pregnant NHB women were recruited by trained recruitment specialists in prenatal clinics serving two hospitals in primal N Carolina. Eligible women were English-speaking, 18–39 years, < 28 weeks' gestation, expecting a singleton pregnancy, planning to stay in the expanse, and willing to identify a study partner, an "other." At baseline, mothers identified a written report partner by answering the question, "Who is the person, other than a doctor or healthcare professional, that is nigh important to your determination-making nearly infant care or that volition be involved in caring for the infant during the kickoff few months after his/her nascency?" Labor and delivery (L&D) exclusion criteria were multiple birth, premature nascence (< 36 weeks), mother or babe having a hospital stay > 7 days after commitment, birthweight < 2500 g, or diagnosis of a condition significantly affecting feeding or growth.

Interventions

Participants in the obesity prevention grouping (OPG) received 8 home visits, an information toolkit, and 4 newsletters designed to provide anticipatory guidance (AG) and support for enactment of six targeted baby feeding and intendance behaviors: breastfeeding (EBF until 6 months, continued BF until 12 months); adoption of a responsive feeding mode; use of non-food soothing techniques for infant crying; advisable timing and quality of CF; minimization of TV/media; and, promotion of age-appropriate infant slumber. Six home visits were delivered by a PE at 30- and 34-weeks gestation and 3-, six-, 9-, and 12-months postpartum. PEs were AA women who were required to take a MS/MPH degree in a health-related field or a BS/BA degree in a wellness-related field plus two or more than years of experience providing individual or grouping counseling. Additionally, the PE for the intervention grouping had breastfed her own children and received over 100 h of training in breastfeeding, CF, and infant beliefs during the outset 6 months of study preparation. Intervention families could receive upward to two additional dwelling house visits by an International Board Certified Lactation Consultant (LC) after hospital discharge, at any time of their choosing. The AG curriculum, described previously in particular [32], was informed by multiple practiced resources, including the Baby Beliefs program [33], Ages & Stages Learning Activities [34], the Start Healthy Feeding Guidelines [35], and the American Academy of Pediatrics Nutrition Handbook [36].

Content for the injury prevention group (IPG) was based on the injury prevention AG published in AAP Bright Futures [37]. An attention-control design was chosen to control for differences in social support provided by the PE, while providing content unrelated to the targeted health behaviors. Women received the same number of habitation visits, a toolkit, and newsletters. The PE for the control group had previous experience in the supervision of young children and received over 100 h of grooming during the study preparation phase in the prevention of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome, proper installation of baby car safety seats, and household injury prevention measures. While women in both groups identified a study partner, IPG partners only completed study assessments; they were not encouraged to attend domicile visits or given their own set of written report materials. An overview of the content for each handling group is provided as supplemental cloth (Supplemental Table one).

Randomization and data collection

Due to the influence of infirmary practices on breastfeeding outcomes [38], randomization was stratified by hospital—each prenatal dispensary served one large, metropolitan hospital—using a computer-generated sequence, cake size of 50, and 1:one allocation ratio. The projection manager, who had no direct contact with participants, was responsible for generating the random number table and uploading it to REDCap [39], a secure, online database maintained by the North Carolina Center for Translational and Clinical Sciences Institute. After completing the baseline cess, the PE randomized the participant using the randomization functionality in REDCap. Blinding was not maintained for PEs and participants later on treatment resource allotment, as participants were made aware of the intervention groups during the consent process and PEs delivered the differing intervention content.

Measures

Background characteristics

Maternal, report partner, and household demographic information was collected at baseline. Participants self-identified their race/ethnicity using categories in the National Wellness and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). For labor and commitment information, research assistants in the prenatal clinics monitored hospital deliveries and promptly notified study staff, who administered a brief survey to mothers, inclusive of baby sex, gestational age, birthweight, and presence of L&D exclusion criteria. Depression was measured using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies – Low (CES-D) scale, with presence of depressive symptoms defined as a score of xvi or higher [40, 41].

Outcome

The primary outcome listed in the protocol and trial registration was lower weight-for-length z-score (WLZ) at 15 months, smaller change in WLZ between 0 and xv months, and lower likelihood of overweight (WLZ ≥ 95th percentile) at xv months. All z-scores, including weight-for-historic period (WAZ) and length-for-age (LAZ), were calculated using the World Health Organization 2006 international growth standards [42]. Baby birth weight and length were cocky-reported by mothers during a telephone-based survey, which was administered shortly later birth to assess connected eligibility. Anthropometrics at subsequent fourth dimension points were directly measured by the one PE assigned to the corresponding handling group. Each PE had prior feel in enquiry-related anthropometric measurement and received approximately 16 h of boosted training at report get-go in guidelines used in NHANES [43]. Babe weight was measured on a digital scale (Tanita BD-585 Digital Baby Scale) to the nearest x 1000. Recumbent length was measured to the nearest 0.ane cm using a portable length board (O'Leary Length Lath). All anthropometrics were done in triplicate and their hateful was used in assay. Despite PEs being trained and achieving strong inter-rater reliability, in that location were systematic differences in LAZ between treatment groups, with OPG infants significantly shorter at multiple time points. The relative technical error of measurement (TEM) for LAZ was 0.12 and 0.08% for the OPG PE and IPG PE, respectively. The relative TEM remained loftier from the initial iii-month visit (OPG = 0.xiii% and IPG = 0.05%) to the final 15-month visit (OPG = 0.10% and IPG = 0.10%). Given the difference in LAZ, the analysis of the primary consequence proceeded with WAZ, including the mean divergence in WAZ between treatment groups and proportion overweight, defined equally WAZ ≥2 SD of the WHO 2006 international growth standards [forty]. Results for WLZ are likewise presented for the reader.

Sample size and Power calculation

The target sample size was 468 families based on power analyses showing a minimum of 354 mother-infant pairs (177 per group) would allow detection of an effect size of ≥0.30 in babe WLZ at 15 months. This was based on an estimated hateful WLZ of 0.34 ± ane.04 SD from our preliminary observational cohort study [sixteen, 25, 28, 44]. To achieve the minimum sample size of 354 infants at report terminate, nosotros incorporated a 12% loss of mothers due to L&D criteria and 20% due to attrition.

Statistical assay

Descriptive statistics by visit and handling group were run for all variables. Differences betwixt treatment groups in baseline characteristics and completers and non-completers of domicile visits were tested using chi-square for dichotomous and ANOVA for continuous variables. All primary analyses were conducted on an Intent-to-Treat (ITT) ground. Randomized subjects who experienced any Fifty&D exclusion criteria were not included in the analyses.

To test the impact of the intervention on baby WAZ, we used a serial of cross-sectional, multivariable, linear regression models. For each model, WAZ was entered as the dependent variable and treatment indicator as the contained variable. A linear mixed effects model was used to test whether the weight trajectories differed between the two treatment groups. The longitudinal WAZ score between groups at birth, iii-, 6-, 9-, 12- and 15-months was the dependent variable and treatment indicator, visit fourth dimension, and treatment-by-time interaction were independent variables. To examine the effects of the intervention on the tails of the WAZ distribution, a three-level categorical variable was created based on initial weight condition at nascence ("lower birth WAZ" if nascency WAZ was at or below − one SD, "middle nascency WAZ" if birth WAZ was between − 1 SD and + ane SD, and "upper nascency WAZ" if birth WAZ was at or to a higher place + i SD). A multivariable, linear regression model was run with change in WAZ between nativity to fifteen months every bit the dependent variable and treatment, categorical size at birth (lower, middle, or upper WAZ), and treatment-past-size interaction every bit the independent variables. To examine the furnishings of the intervention on WAZ by dose received, all models were repeated every bit non-ITT, in which dose was entered as a continuous independent variable ranging from 0 to six, based on the number of educational habitation visits the participant completed. Finally, models also tested for differences past type of study partner.

All models were first run unadjusted, followed by an adjusted model, which included breastfeeding condition as a covariate and any variables establish significantly unlike between treatment groups at baseline or between completers and non-completers of home visits. Finally, multiple imputation using multivariate normal regression was used to business relationship for missing data in each of the multivariable, cantankerous-sectional models and the linear regression model examining change in WAZ betwixt birth to 15 months; the linear mixed furnishings model accounts for missingness, rendering imputation unnecessary. While missing observations tin can lead to less precision, including larger standard errors and less power, equally well as biased parameter estimates, there were no differences in the parameter estimates and levels of significance between our imputation and complete-case models; thus simply the results of the complete-case analysis are shown. Further, we were unable to place whatsoever auxiliary variables with a correlation > 0.4, adding forcefulness to the assumption that the data are missing at random (MAR). Stata v15 was used for all analyses. Significance was set at P < .05.

Results

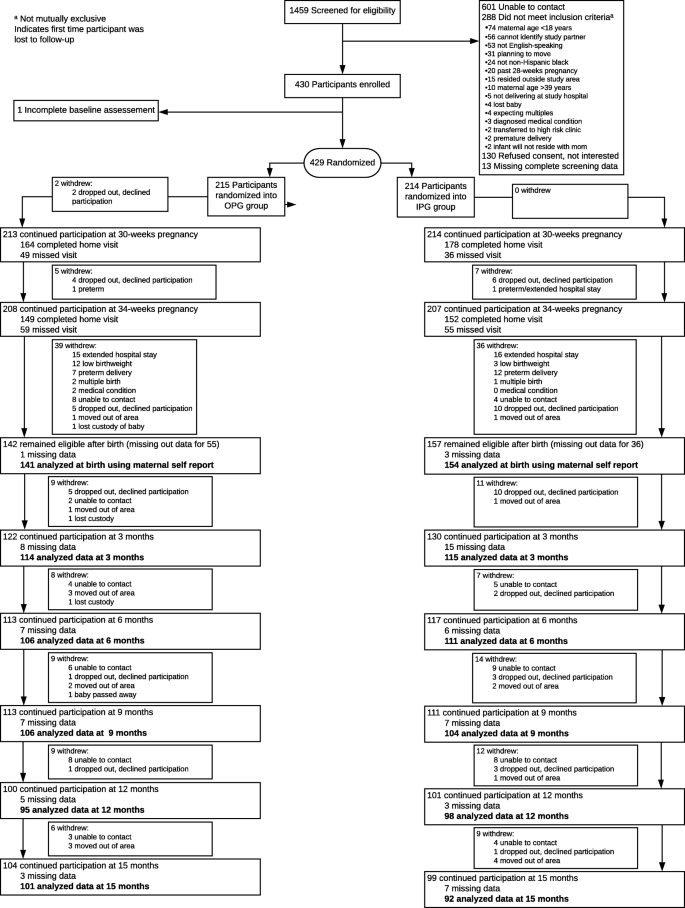

Approximately 1575 women were screened in prenatal clinics, of which 1031 were eligible, although the majority (north = 601) could not be reached to arrange a baseline visit (Fig. 1). Four hundred and 30 women provided consent and were enrolled. One adult female did non complete the baseline assessment and was not randomized and one adult female was missing baseline sociodemographic information. There were no significant differences between groups in sample characteristics at baseline or in birthweight or Caesarian delivery (Table 1); even so, there were differences between completers and non-completers in maternal age, pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI), and marital condition (Supplemental Table two).

Menstruum diagram. aNon mutually exclusive. bIndicates get-go fourth dimension that participant was lost to follow-up

On average, women were in their mid-twenties, had prior children, entered pregnancy with an overweight BMI, had no higher education, and were single. Almost one-3rd of the women reported depressive symptoms. The highest rate of withdrawal from the study was before 3-months postpartum (Fig. 1). The well-nigh mutual reasons were extended hospital stay (n = 28), refusal to continue participating (n = 27), loss to follow-up (north = 21), and preterm delivery (n = 20).

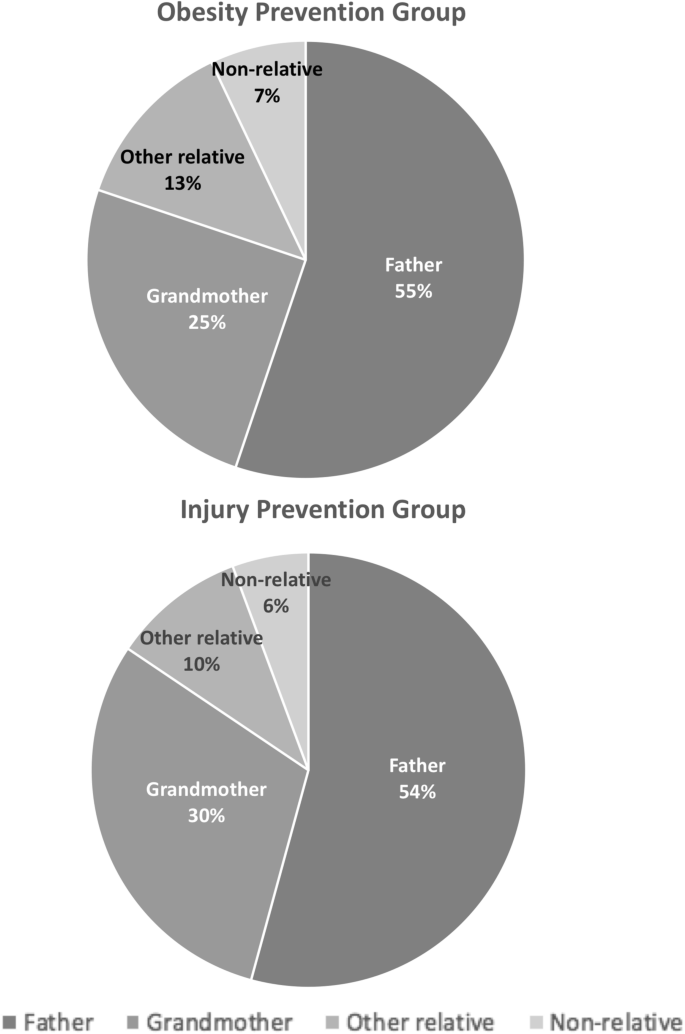

At baseline, approximately half of women chose the infant's male parent (54.6%) as their study partner, 27.5% chose the babe'south grandmother, 11.5% chose another type of relative, and 6.4% chose a nonrelative. Among the 49 women who chose an 'other relative,' 29 chose the babe'south aunt, three chose the infant's cousin, 3 chose the infant's grandfather, 1 chose the babe'southward sister, and thirteen declined to specify the type of 'other relative.' Of the 27 women who chose a nonrelative, five, two, 1, and 19 chose a roommate, the infant'due south godmother, a female person partner, or declined to specify the type of nonrelative, respectively. Women'south choice of study partner was similar in both treatment groups (Fig. 2).

Type of study partner, by treatment grouping

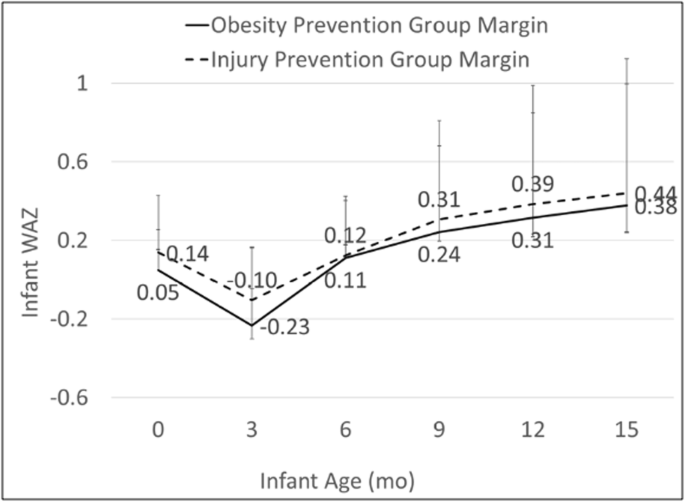

At each fourth dimension bespeak, OPG infants had smaller mean WAZ scores than IPG infants, merely none of the differences were statistically meaning in either unadjusted or adjusted models (Table 2). A similar pattern for WAZ was seen in longitudinal models, with OPG infants demonstrating smaller, but not significant, hateful WAZ scores than IPG infants (Fig. three). Conversely, the proportion of infants categorized every bit overweight (WAZ ≥ ii SD WHO) was higher, simply non significantly and then, at each time point (Tabular array 3). In that location were also no significant differences between groups in models examining the effect of the intervention according to categorical size (lower, eye, or upper WAZ) at birth or by type of study partner (information non shown).

Results of adjusted mixed furnishings modela,b examining WAZ by time and treatment. aModel was adjusted for variables institute to be significantly associated with the completion of whatever home visit and included maternal age, pre-pregnancy BMI, and marital condition. The model likewise included breastfeeding condition as a time-varying covariate. b95% confidence intervals: Birth [OPG (− 0.11, 0.21), IPG (− 0.01, 0.29)], three months [OPG (− 0.40, − 0.07), IPG (− 0.27, 0.06)], 6 months [OPG (− 0.07, 0.29), IPG (− 0.05, 0.xxx)], nine months [OPG (0.05, 0.44), IPG (0.11, 0.l)], 12 months [OPG (0.10, 0.53), IPG (0.17, 0.60)], and 15 months [OPG (0.14, 0.62), IPG (0.twenty, 0.68)]

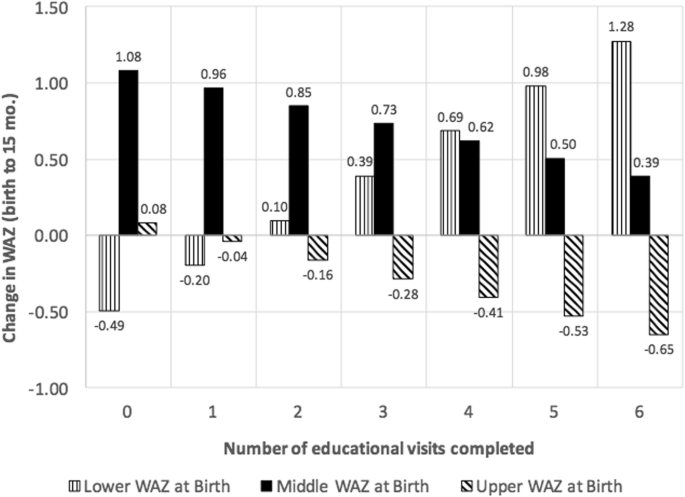

In not-ITT models (Fig. 4), infants who were in the upper end of the WAZ distribution at nascency and whose mothers completed one or more visits, experienced reductions in WAZ between nascency and fifteen months. The size of the reduction in WAZ was greater for each additional visit completed. A similar, inverse pattern was seen for infants in the lower range of the WAZ distribution at birth. Infants in the middle range of the WAZ distribution at birth demonstrated positive mean increases in WAZ, but the increase was smaller for each boosted educational home visit completed. Notwithstanding, the overall examination of the interaction between WAZ category at birth and number of visits completed was not statistically significant (F 2,170 = one.41, p = 0.25).

Results of adjusted linear regression modela examining change in WAZ between birth and 15 months by initial size category at nativity and intervention dose. aModel was adapted for variables found to exist significantly associated with the completion of any abode visit and included maternal age, pre-pregnancy BMI, and marital condition. The model was also adjusted for breastfeeding duration

Discussion

Mothers & Others was an efficacy-trial of a habitation-based intervention designed to prevent obesity in the starting time year of life. Enrollment was limited to NHB, pregnant women, the majority of which were classified as depression-income and unmarried. Women chose a variety of written report partners, most commonly the father and grandmother, but also aunts, cousins, grandfathers, siblings, roommates, and female person partners. Although infants in the intervention group demonstrated lower mean WAZ at all cess time points, the differences were small and did not reach statistical significance.

Our results add to similar findings from RCTs [45,46,47] targeting population groups at college risk of obesity. While income was not an inclusion criterion for Mothers & Others, approximately 75% of our participants were receiving Medicaid. Two prior studies [45, 46] conducted among women participating in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Plan for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), a federal nutrition assistance plan for meaning and postpartum women, infants, and children nether the historic period of five whose household income is ≤185% of the poverty level, documented similar nada findings. Kavanagh et al. [45] targeted exclusively formula-fed infants by providing mothers a single group session covering satiety cues and educational activity to feed infants nether the age of 4 months less than vi fluid ounces per feeding. Mothers were as well given teaching on non-food techniques for soothing a crying baby [48]. At approximately 4-months-old, infants in their intervention group had gained significantly more weight than infants in their control group (195.3 ± 10.0 grand vs 156.i ± 9.5 g, respectively, p = .008).

In a study similar in design to Mothers & Others, Reifsnider et al. (2018) [49] targeted infants of obese, Hispanic, meaning women enrolled in WIC. The intervention consisted of viii home visits delivered by peer educators, or "promotorás," who charted infant weight and length and provided advice on baby feeding, play, and sleep. Mothers could as well request the services of a LC. At 12 months of historic period, there were no differences between infants in the intervention versus control group in WLZ or proportion of infants classified equally overweight or obese [46].

In the Australian written report, Healthy Ancestry, Wen et al. [50] targeted all pregnant women attending antenatal clinics serving a disadvantaged population. The intervention group received eight postpartum home visits from a customs wellness nurse. At 2 years of age, in that location was a small, statistically meaning difference in BMI between children in the intervention and command grouping (BMIdiff = − 0.29, 95% CI: − 0.55, − 0.02) [47]. An important difference betwixt Healthy Ancestry and Mothers & Others is the proportion of women who were married: 90% versus 28%, respectively. Single mothers often report college levels of stress than do married mothers [51], with higher maternal stress associated with more decision-making feeding practices [52] and kid weight status [53, 54], particularly among NHB children and children from low-income families [55].

Results from RCTs [56,57,58,59,60,61] conducted among more economically advantaged populations have been mixed. Two trials [62, 63] in Commonwealth of australia, each utilizing first-time parent groups to evangelize AG on infant feeding and physical action betwixt approximately four–18 months postpartum, produced null findings [56, 57, 60]. Conversely, two trials, POI in New Zealand [64] and INSIGHT in the U.S. [65], both of which delivered the intervention through habitation visits from enquiry nurses and had a strong component on infant sleep, documented positive outcomes for infant size and growth [58, 59, 61]. Of note, the majority of participants in each of these studies had attended higher (76% in POI and xc% in INISGHT), and 75% of the mothers in INSIGHT were married. Thus, habitation visits past research nurses appear a promising strategy amongst more economically advantaged or married, NHW populations. It is non known if such interventions are effective amongst lower-income or racially diverse populations.

A novel component of Mothers & Others was the active inclusion of a study partner in the intervention group; however, our results suggest support provided by the PEs was beneficial in both arms. Prior studies [66, 67] of organized peer back up, especially among low-income and minority women, have shown it to reduce social isolation, provide validation of parenting practices, and enhance the emotional well-beingness of mothers. It is possible that organized peer support, regardless of the topic, may be benign for obesity prevention through its function in enhancing maternal emotional well-being. Inquiry appropriately designed to test this hypothesis is needed.

It is as well of import to notation the multicomponent design of the trials published to date as well equally the seemingly different developmental philosophies occurring across, and within, trials. The Multiphase Optimization Strategy, or MOST, is a framework for optimizing the design of behavioral interventions [68]. Inspired by engineering, MOST encourages designs, often a factorial experiment, which tin can isolate the outcome of individual intervention components. In Mothers & Others, a factorial experiment could accept yielded individual main furnishings for components, and interactions between components, such every bit those designed to promote responsive feeding versus those targeting maternal social support. It is possible some content in Mothers & Others had no effect or was even antagonistic; this is of import information for moving the science forrard.

For future research, we also believe information technology of import to test the seemingly dissimilar developmental approaches trials have used to address infant fussing and crying. For case, one could test the divergence in helping parents understand what their infant is communicating, thereby promoting the developmental philosophy of mind-mindedness [69], versus provision of strategies to minimize crying [48]. Meins et al. (2001) define listen-mindedness as "the mother'due south proclivity to treat her infant as an individual with a mind, rather than merely as a creature with needs that must be satisfied" (p. 638) [70]. A substantial trunk of research has demonstrated positive associations between parental heed-mindedness and child attachment [71,72,73], emotion regulation [74], and executive functioning [75, 76], also equally maternal responsive feeding behaviors [77]. Given its import to multiple domains of kid evolution, it seems judicious to examination the extent to which dissimilar intervention approaches touch both mind-mindedness and weight status.

Mothers & Others contained several limitations. First, nosotros did not report WLZ, given the systematic differences in length between the two arms. Because the Foot each collected anthropometric measurements of infants in their respective arms, we cannot exist certain whether the differences in length were due to biological differences or differences in measurement. Having the PEs collect the anthropometric data also raises a concern for bias. However, several lines of reasoning and examination point to differences in measurement technique rather than bias. The length of time between visits (3 months) makes it unlikely that PEs remembered infant weight or length values at prior visits. Also, the fact that the error was in length rather than weight variables makes it unlikely that bias, rather than differences in technique, contributed to the systematic mistake. Further, the intra-rater reliability was very high for both PEs and remained high from the initial to last visits, suggesting that drift in technique was also not the cause of the differences between groups. All other measures were completed prior to the abode visit via online (majority) or mailed surveys. Second, birthweight information was planned to be nerveless from the medical record by trained research staff in our research network. This staff was as well responsible for screening and recruitment, which took longer than anticipated, thus exhausting funds for medical record extraction. Third, generalizability of our findings is limited to predominately low-income, NHB women; however, this is an important population for early life obesity prevention. Finally, attrition was loftier in Mothers & Others, although not differential across treatment arms, and may accept limited power to detect differences in infant size and growth. In their study of low-income, Hispanic mother-babe dyads, Reifsnider et al. [46] reported a like rate of retentivity (64%) at 12 months. Together, these trials provide of import data on recruitment and retentivity for future studies targeting similar income and racial/ethnic populations. Examination of secondary outcomes, including maternal and study partner behaviors related to infant feeding, motion, and screen exposure are underway, as are analyses of mediators (east.thou. change in knowledge, infant feeding styles, and babe feeding attitudes). Data on injury prevention practices were likewise collected and may be examined to make up one's mind the efficacy of the attention-command group in this regard.

Conclusions

Mothers & Others did not produce meaning differences in babe size or growth during the starting time 15 months of life, a result consistent with other trials conducted among low-income, minority populations in the US, of which at that place have been few. Although we recruited a large sample and had loftier retentivity during the postpartum period, there was loftier attrition betwixt the concluding prenatal and kickoff postpartum dwelling house visit. Boosted home visits by the PE, a person with which the mothers had built rapport, earlier in the postpartum period may be a critical component for future studies. Indeed, our finding in both groups of positive, incremental effects on infant size by number of PE dwelling visits received suggests an important role of organized peer back up, regardless of the content provided. Finally, that women chose a variety of study partners, including but not express to fathers and grandmothers, suggests a need for interventions and observational inquiry that recognize the varied circumstances of women.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset used and analyzed during the current report is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AG:

-

Anticipatory guidance

- BF:

-

Breastfeeding

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CF:

-

Complementary foods

- EBF:

-

Exclusive breastfeeding

- INSIGHT:

-

Intervention Nurses Showtime Infants Growing on Good for you Trajectories

- IPG:

-

Injury prevention group

- ITT:

-

Intent-to-treat

- L&D:

-

Labor and delivery

- LAZ:

-

Length-for-historic period z-score

- LC:

-

Lactation consultant

- MOST:

-

Multiphase Optimization Strategy

- NHANES:

-

National Wellness and Nutrition Examination Survey

- NHB:

-

Non-Hispanic black

- NHW:

-

Non-Hispanic white

- OPG:

-

Obesity prevention grouping

- PE:

-

Peer educator

- POI:

-

Prevention of Overweight in Infancy

- RCT:

-

Randomized controlled trial

- WAZ:

-

Weight-for-age z-score

- WLZ:

-

Weight-for-length z-score

- WIC:

-

Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children

References

-

Ogden CL, Flegal KM, Carroll Doc, Johnson CL. Prevalence and trends in overweight among U.s. children and adolescents, 1999-2000. JAMA. 2002;288(14):1728–32.

-

Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the Us, 2011-2012. JAMA. 2014;311(viii):806–xiv.

-

Woo Baidal JA, Locks LM, Cheng ER, Blake-Lamb TL, Perkins ME, Taveras EM. Risk factors for childhood obesity in the kickoff 1,000 days: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2016;50(vi):761–79.

-

Simmonds M, Llewellyn A, Owen CG, Woolacott N. Predicting adult obesity from childhood obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2016;17(2):95–107.

-

Llewellyn A, Simmonds M, Owen CG, Woolacott N. Childhood obesity as a predictor of morbidity in adulthood: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2016;17(1):56–67.

-

Prospective Studies Collaboration, Whitlock G, Lewington S, Sherliker P, Clarke R, Emberson J, et al. Body-mass index and cause-specific mortality in 900 000 adults: collaborative analyses of 57 prospective studies. Lancet. 2009;373(9669):1083–96.

-

Victora CG, Bahl R, Barros AJD, França GVA, Horton Southward, Krasevec J, et al. Breastfeeding in the 21st century: epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. Lancet. 2016;387(10017):475–90.

-

Agostoni C, Przyrembel H. The timing of introduction of complementary foods and later wellness. World Rev Nutr Diet. 2013;108:63–70.

-

Fewtrell MS. Can optimal complementary feeding ameliorate later health and evolution? Nestle Nutr Inst Workshop Ser. 2016;85:113–23.

-

Taveras EM, Rifas-Shiman SL, Oken East, Gunderson EP, Gillman MW. Short slumber elapsing in infancy and risk of childhood overweight. Curvation Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008;162(four):305–eleven.

-

Taveras EM, Gillman MW, Peña M-M, Redline S, Rifas-Shiman SL. Chronic slumber curtailment and adiposity. Pediatrics. 2014;133(6):1013–22.

-

Fletcher S, Wright C, Jones A, Parkinson One thousand, Adamson A. Tracking of toddler fruit and vegetable preferences to intake and adiposity later on in childhood. Matern Child Nutr. 2017;13(2):e12290.

-

Pan Fifty, Li R, Park Southward, Galuska DA, Sherry B, Freedman DS. A longitudinal analysis of sugar-sweetened drink intake in infancy and obesity at 6 years. Pediatrics. 2014;134(Suppl 1):S29–35.

-

Sonneville KR, Long MW, Rifas-Shiman SL, Kleinman K, Gillman MW, Taveras EM. Juice and water intake in infancy and after drinkable intake and adiposity: could juice be a gateway potable? Obesity (Silvery Spring). 2015;23(i):170–vi.

-

Saavedra JM, Deming D, Dattilo A, Reidy K. Lessons from the feeding infants and toddlers study in Due north America: what children eat, and implications for obesity prevention. Ann Nutr Metab. 2013;62(Suppl 3):27–36.

-

Thompson AL, Adair LS, Bentley ME. Maternal characteristics and perception of temperament associated with infant Television set exposure. Pediatrics. 2013;131(two):e390–7.

-

Cespedes EM, Gillman MW, Kleinman One thousand, Rifas-Shiman SL, Redline South, Taveras EM. Idiot box viewing, bedroom television, and slumber duration from infancy to mid-childhood. Pediatrics. 2014;133(5):e1163–71.

-

Certain LK, Kahn RS. Prevalence, correlates, and trajectory of television viewing amid infants and toddlers. Pediatrics. 2002;109(4):634–42.

-

de Jager E, Broadbent J, Fuller-Tyszkiewicz M, Skouteris H. The role of psychosocial factors in sectional breastfeeding to six months postpartum. Midwifery. 2014;30(half dozen):657–66.

-

Nnebe-Agumadu UH, Racine EF, Laditka SB, Coffman MJ. Associations betwixt perceived value of exclusive breastfeeding amidst pregnant women in the The states and exclusive breastfeeding to 3 and vi months postpartum: a prospective study. Int Breastfeed J. 2016;11:8.

-

Roll CL, Cheater F. Expectant parents' views of factors influencing baby feeding decisions in the antenatal period: a systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2016;sixty:145–55.

-

Emmott EH, Mace R. Practical back up from fathers and grandmothers is associated with lower levels of breastfeeding in the UK millennium cohort report. PLoS One. 2015;10(7):e0133547.

-

Cisco J. Who supports breastfeeding mothers? : An investigation of kin investment in the United States. Hum Nat. 2017;28(ii):231–53.

-

Chapman DJ, Pérez-Escamilla R. Breastfeeding amidst minority women: moving from risk factors to interventions. Adv Nutr. 2012;3(i):95–104.

-

Thompson AL, Mendez MA, Borja JB, Adair LS, Zimmer CR, Bentley ME. Development and validation of the infant feeding style questionnaire. Appetite. 2009;53(two):210–21.

-

Hurley KM, Cantankerous MB, Hughes SO. A systematic review of responsive feeding and child obesity in high-income countries. J Nutr. 2011;141(three):495–501.

-

Heinig MJ, Follett JR, Ishii KD, Kavanagh-Prochaska K, Cohen R, Panchula J. Barriers to compliance with infant-feeding recommendations amidst low-income women. J Hum Lact. 2006;22(1):27–38.

-

Wasser H, Bentley Yard, Borja J, Davis Goldman B, Thompson A, Slining M, et al. Infants perceived every bit "fussy" are more than likely to receive complementary foods before 4 months. Pediatrics. 2011;127(2):229–37.

-

Stifter CA, Moding KJ. Infant temperament and parent use of nutrient to soothe predict change in weight-for-length beyond infancy: early adventure factors for babyhood obesity. Int J Obes. 2018;42(nine):1631–8.

-

Taveras EM, Gillman MW, Kleinman K, Rich-Edwards JW, Rifas-Shiman SL. Racial/ethnic differences in early-life run a risk factors for childhood obesity. Pediatrics. 2010;125(four):686–95.

-

Anstey EH, Chen J, Elam-Evans LD, Perrine CG. Racial and geographic differences in breastfeeding - U.s., 2011-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(27):723–7.

-

Wasser HM, Thompson AL, Suchindran CM, Hodges EA, Goldman BD, Perrin EM, et al. Family-based obesity prevention for infants: design of the "mothers & others" randomized trial. Contemp Clin Trials. 2017;lx:24–33.

-

Heinig MJ, Banuelos J, Goldbronn J, Kamp J. Fit WIC baby beliefs study: helping you understand your baby [Internet]. 2006 WIC Special Project Grants | USDA-FNS. [cited 2020 Aug 10]. Available from: https://www.fns.usda.gov/wic/2006-wic-special-project-grants.

-

Brookes Publishing. Ages & Stages Questionnaires (ASQ) Learning Activities [Internet]. Available from: https://agesandstages.com/products-pricing/learning-activities/. Accessed 10 Aug 2020.

-

Butte Due north, Cobb One thousand, Dwyer J, Graney L, Heird W, Rickard Yard, et al. The start good for you feeding guidelines for infants and toddlers. J Am Nutrition Assoc. 2004;104(iii):442–54.

-

Pediatric Nutrition, seventh Edition [eBook] - AAP. [cited 2019 Jul 25]. Available from: https://shop.aap.org/pediatric-nutrition-7th-edition-ebook/?gclid=EAIaIQobChMIv_XM6ajQ4wIVBl8NCh3ssg38EAAYASAAEgJv_fD_BwE.

-

Hagan JF, Shaw JS, Duncan PM. Vivid futures: guidelines for health supervision of infants, children, and adolescents. 3rd ed. Elk Grove Village: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2008.

-

Pérez-Escamilla R, Martinez JL, Segura-Pérez Due south. Impact of the babe-friendly hospital initiative on breastfeeding and child health outcomes: a systematic review. Matern Child Nutr. 2016;12(three):402–17.

-

Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Enquiry electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow procedure for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(ii):377–81.

-

Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1(three):385–401.

-

Atkins R. Validation of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale in black single mothers. J Nurs Meas. 2014;22(3):511–24.

-

Grummer-Strawn LM, Reinold C, Krebs NF, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Use of World Health System and CDC growth charts for children anile 0–59 months in the United states. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-ix):one–15.

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Health and Nutrition Exam Survey Anthropometry Protocol. 2013.

-

Thompson AL, Bentley ME. The critical catamenia of babe feeding for the development of early disparities in obesity. Soc Sci Med. 2013;97:288–96.

-

Kavanagh KF, Cohen RJ, Heinig MJ, Dewey KG. Educational intervention to modify bottle-feeding behaviors among formula-feeding mothers in the WIC program: touch on on infant formula intake and weight gain. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2008;xl(4):244–50.

-

Reifsnider Due east, McCormick DP, Cullen KW, Todd M, Moramarco MW, Gallagher MR, et al. Randomized controlled trial to forbid infant overweight in a high-run a risk population. Acad Pediatr. 2018;18(three):324–33.

-

Wen LM, Baur LA, Simpson JM, Rissel C, Wardle Grand, Flood VM. Effectiveness of habitation based early intervention on children'south BMI at age 2: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2012;344:e3732.

-

Karp H. Happiest Babe. [cited 2019 Jul 26]. Available from: https://www.happiestbaby.com/blogs/baby/the-5-s-s-for-soothing-babies.

-

Reifsnider E, McCormick DP, Cullen KW, Szalacha L, Moramarco MW, Diaz A, et al. A randomized controlled trial to prevent babyhood obesity through early babyhood feeding and parenting guidance: rationale and blueprint of study. BMC Public Wellness. 2013;thirteen:880.

-

Wen LM, Baur LA, Rissel C, Wardle K, Alperstein G, Simpson JM. Early on intervention of multiple home visits to preclude childhood obesity in a disadvantaged population: a habitation-based randomised controlled trial (healthy beginnings trial). BMC Public Health. 2007;7:76.

-

Avison WR, Ali J, Walters D. Family structure, stress, and psychological distress: a sit-in of the impact of differential exposure. J Health Soc Behav. 2007;48(iii):301–17.

-

Hughes Then, Power TG, Liu Y, Abrupt C, Nicklas TA. Parent emotional distress and feeding styles in low-income families. The function of parent depression and parenting stress. Appetite. 2015;92:337–42.

-

Shankardass K, McConnell R, Jerrett M, Lam C, Wolch J, Milam J, et al. Parental stress increases body mass index trajectory in pre-adolescents. Pediatr Obes. 2014;nine(6):435–42.

-

Rondó PHC, Rezende G, Lemos JO, Pereira JA. Maternal stress and distress and child nutritional status. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2013;67(four):348–52.

-

Baskind MJ, Taveras EM, Gerber MW, Fiechtner L, Horan C, Sharifi M. Parent-perceived stress and its association with Children'south weight and obesity-related behaviors. Prev Chronic Dis. 2019;16:E39.

-

Daniels LA, Mallan KM, Nicholson JM, Battistutta D, Magarey A. Outcomes of an early feeding practices intervention to prevent babyhood obesity. Pediatrics. 2013;132(1):e109–xviii.

-

Daniels LA, Mallan KM, Nicholson JM, Thorpe K, Nambiar S, Mauch CE, et al. An early feeding practices intervention for obesity prevention. Pediatrics. 2015;136(one):e40–nine.

-

Barbarous JS, Birch LL, Marini Thou, Anzman-Frasca S, Paul IM. Effect of the INSIGHT responsive parenting intervention on rapid infant weight proceeds and overweight condition at age i year: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(8):742–9.

-

Paul IM, Savage JS, Anzman-Frasca S, Marini ME, Beiler JS, Hess LB, et al. Upshot of a responsive parenting educational intervention on childhood weight outcomes at 3 years of age: the INSIGHT randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;320(v):461–8.

-

Campbell KJ, Lioret Due south, McNaughton SA, Crawford DA, Salmon J, Brawl K, et al. A parent-focused intervention to reduce infant obesity chance behaviors: a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2013;131(4):652–60.

-

Taylor BJ, Grey AR, Galland BC, Heath A-LM, Lawrence J, Sayers RM, et al. Targeting sleep, nutrient, and activeness in infants for obesity prevention: an RCT. Pediatrics. 2017;139(3):e20162037.

-

Daniels LA, Magarey A, Battistutta D, Nicholson JM, Farrell A, Davidson Thousand, et al. The NOURISH randomised command trial: positive feeding practices and food preferences in early on babyhood - a primary prevention program for childhood obesity. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:387.

-

Campbell G, Hesketh Chiliad, Crawford D, Salmon J, Ball K, McCallum Z. The baby feeding activity and Nutrition trial (INFANT) an early intervention to foreclose childhood obesity: cluster-randomised controlled trial. BMC Public Health. 2008;viii:103.

-

Taylor BJ, Heath A-LM, Galland BC, Grey AR, Lawrence JA, Sayers RM, et al. Prevention of Overweight in Infancy (POI.nz) study: a randomised controlled trial of sleep, food and activity interventions for preventing overweight from birth. BMC Public Health. 2011;xi:942.

-

Paul IM, Williams JS, Anzman-Frasca Due south, Beiler JS, Makova KD, Marini ME, et al. The intervention nurses start infants growing on healthy trajectories (INSIGHT) study. BMC Pediatr. 2014;14:184.

-

Jones CCG, Jomeen J, Hayter M. The bear on of peer support in the context of perinatal mental illness: a meta-ethnography. Midwifery. 2014;30(5):491–8.

-

McLeish J, Redshaw K. Mothers' accounts of the impact on emotional wellbeing of organised peer support in pregnancy and early parenthood: a qualitative study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17(1):28.

-

Collins LM. Optimization of behavioral, biobehavioral, and biomedical interventions. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2018.

-

Meins E. Security of zipper and the social evolution of cognition (essays in Developmental Psychology). 1st ed. East Sussex: Psychology Press; 1997.

-

Meins E, Fernyhough C, Fradley Due east, Tuckey M. Rethinking maternal sensitivity: mothers' comments on infants' mental processes predict security of attachment at 12 months. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2001;42(v):637–48.

-

Laranjo J, Bernier A, Meins E. Associations between maternal mind-mindedness and infant attachment security: investigating the mediating function of maternal sensitivity. Babe Behav Dev. 2008;31(4):688–95.

-

Miller JE, Kim S, Boldt LJ, Goffin KC, Kochanska Thou. Long-term sequelae of mothers' and fathers' mind-mindedness in infancy: a developmental path to children's attachment at age x. Dev Psychol. 2019;55(4):675–86.

-

Zeegers MAJ, de Vente Due west, Nikolić M, Majdandžić M, Bögels SM, Colonnesi C. Mothers' and fathers' mind-mindedness influences physiological emotion regulation of infants across the first yr of life. Dev Sci. 2018;21(vi):e12689.

-

Bernier A, Carlson SM, Whipple N. From external regulation to self-regulation: early parenting precursors of immature children's executive functioning. Child Dev. 2010;81(one):326–39.

-

Meins East, Fernyhough C, Arnott B, Leekam SR, de Rosnay Yard. Mind-mindedness and theory of mind: mediating roles of language and perspectival symbolic play. Child Dev. 2013;84(five):1777–90.

-

McMahon CA, Meins Eastward. Listen-mindedness, parenting stress, and emotional availability in mothers of preschoolers. Early Child Res Q. 2012;27(two):245–52.

-

Farrow C, Blissett J. Maternal mind-mindedness during infancy, general parenting sensitivity and observed child feeding behavior: a longitudinal study. Adhere Hum Dev. 2014;16(3):230–41.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank our peer educators, Kenitra Williams and Tuvara King, and all of our study participants for their fourth dimension and contribution to this study, likewise every bit all of the staff at the Center for Women's Wellness Enquiry at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Funding

This report was supported past the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), National Institutes of Wellness (NIH), through Grant Award Number R01HD073237 and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), NIH, through Grant Honor Number UL1TR001111. NIH had no role in the pattern of the study, data collection, data analysis, writing the manuscript or interpretation of results.

Writer information

Affiliations

Contributions

HW, AT, CS, and MB contributed to the analysis and estimation of the data. HW drafted the manuscript. All authors (HW, AT, CS, BG, EH, MH, and MB) contributed to the study conception and design, provided critical revision of the manuscript, and read and approved the final manuscript.

Respective writer

Ethics declarations

Ideals approval and consent to participate

Institutional review lath blessing was granted by the University of Due north Carolina, Part of Human Research Ideals. Written informed consent was obtained from significant women and study partners prior to their completing the baseline cess. Pregnant women as well provided written informed parent permission for their infant'due south participation.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Admission This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution iv.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other 3rd political party material in this commodity are included in the article's Artistic Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the cloth. If fabric is non included in the article's Creative Eatables licence and your intended employ is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/four.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/ane.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wasser, H.Thousand., Thompson, A.L., Suchindran, C.M. et al. Domicile-based intervention for non-Hispanic black families finds no significant difference in infant size or growth: results from the Mothers & Others randomized controlled trial. BMC Pediatr 20, 385 (2020). https://doi.org/x.1186/s12887-020-02273-nine

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-020-02273-9

Keywords

- Infant feeding

- Sedentary behavior

- Sleep

- Obesity prevention

revelestwomithe1956.blogspot.com

Source: https://bmcpediatr.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12887-020-02273-9

0 Response to "Family-based Obesity Prevention for Infants: Design of the "Mothers & Others" Randomized Trial"

Enregistrer un commentaire